According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the global number of international students keeps increasing year by year, with a rate of 6.4 million students recorded in 2020 (“2023 Key Figures: Europe Is the Leading Host Region for Mobile Students,” n.d.).

Studying Translation as an International Student

Becoming an international student in the translation field implies that one should have been studying at least two foreign languages, and, consequently, they should have reached an advanced level in their translation skills before deciding to move abroad. However, speaking from personal experience, no amount of study and devotion to this field in your home country can prepare you for the experience of living and trying to fit in a different system. Adaptation in a new country has two dimensions: psychological and sociocultural, and I will be addressing both over the following paragraphs.

High Expectations, Language Barrier and Self-Isolation

On the one hand, regarding the psychological dimension, the first factor influencing your perception of the system you are about to enter becomes apparent even before leaving your home country. It is your own perception of the country you wish to move to, which is created based on the ideas promoted in your country. Friends, family, everyone can contribute to the way you form your opinion. For instance, I thought that moving to France would be a dream come true, that the education system would not only be superior to the one in Romania, but it would also meet all my ideological expectations about what an education system should be like. I also thought my life would be happier here, easier from all points of view. I should say that I was only 18 years old when I moved to France, my experience was limited, and my hopes were optimistic, to say the least.

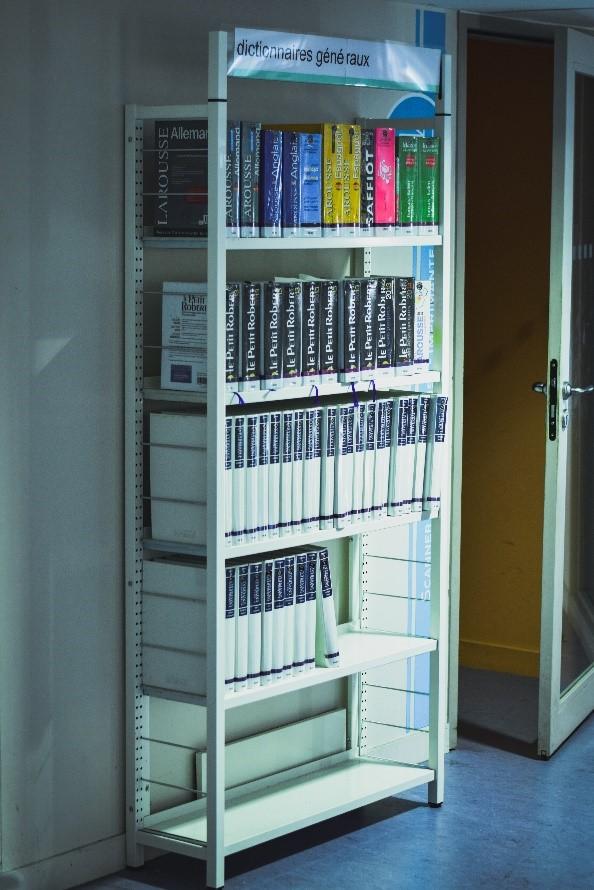

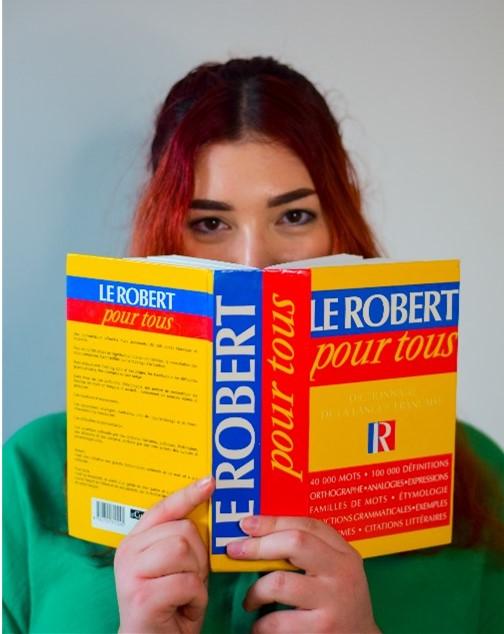

In my case, which, according to Rachel Smith and Nigar Khawaja (2011), is a general perception that international students have, I thought that being a straight-A student in my home country would automatically mean that I would be nothing but successful as a student in France. My delusion was quickly dismantled after I faced the reality of the language barrier, and after I received my first university transcript. Learning in my native language was no longer efficient. So, I had to adapt to learning in French, to push myself more than my peers, who were French natives, and to get lower grades than they would. One of the biggest hardships I had to cope with was that my knowledge in terms of translation, although not necessarily wrong, was incomplete. Despite having dedicated years of my life to learning French, my B2 level was disastrous compared to native speakers’ level. Learning to distinguish between words that I initially learned as synonyms and understanding the different nuances of the French language was a frustrating process. I had to learn again how to translate French, to remember that my initial information was not adequate or not precise enough, and to correct myself time and again. It was a gradual process, and my teachers had to point out my mistakes several times in order for me to integrate the correct version into my memory. It felt discouraging at times to see that I kept making the same mistakes, and it was difficult to abstain from being disappointed with myself for not spotting them before handing in my translations. Treating people with kindness is worth nothing if you don’t give yourself the same courtesy. Smith and Khawaja also claim that “academic stress is likely to be intensified for international students due to the added stressors of second language anxiety and adapting to a new educational environment” (2011, p. 702). I believe this statement to be true since I had never experienced the fear of failing a class before moving to France and it was only amplified by the fear of failing as an international student and going back to Romania as a quitter, a misconception I had at that time.

However, the language barrier didn’t only affect me at an academic level: My social life changed from going out at least three times a week to once a month. Despite having learned French for six years before moving here, I could barely understand what my classmates were saying, and I could not produce a coherent phrase myself. Naturally, I sought to make either English-speaking friends, or Romanian friends. Wenxuan Li says that “racial segregation would hinder the academic performance of international students” and defines racial segregation as the way in which “people from the same country are more likely to stay together” (2022, p. 1179). Limiting my French practice because communication in French was more difficult made me self-isolate, unconsciously, from my classmates. It took me a year to realize that I needed to go the extra mile, to push myself once again if I wanted to really fit in and make a life for myself in this country. Social anxiety is a concept that my generation often uses to describe the fear of being judged or rejected by people, thereby preventing a person from interacting with strangers. I am no foreigner to this concept because I know that at some point, the fear of making a mistake when speaking French was big enough to stop me from even trying to speak it. This phenomenon is also known as language anxiety, and it is defined by MacIntyre as a type of anxiety that involves “worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (1999, p. 27). So, I had to understand that mistakes are actually the best way of learning.

From Culture Shock to Acculturation

On the other hand, as previously stated, adaptation also has a sociocultural dimension. After living in France for five years, the culture shock still manages to surprise me. I remember noticing how the collective behavior of my classmates in France was so much different from that in Romania. Approaching my classmates out of the blue was considered rude whereas in Romania, the simple fact that people were part of the same collective would mean that they belonged, more or less, to the same clique. When you move to a foreign country, there are countless changes you need to adapt to in order to fit in. I learned to accept that different means, in fact, unique, and to love certain aspects of this country because of its diversity.

I remember having difficulties in some of my translation classes where we had transcreation or marketing translation exercises because I couldn’t find an appropriate translation for certain cultural elements that I couldn’t grasp. Translating subtitles also proved to be a challenge because there were slang words in French that I did not understand. Therefore, I could not translate them into English. There were also English words that I knew but could not translate into French because I didn’t know their French equivalents. Being the only person in the class not laughing at a joke because you couldn’t understand the punchline was not so bad once the punchline had been explained. I understood that if I wanted to be a good translator, I could not limit myself to studying just the language: I had to dive into the culture, the traditions, the way of life. It only made me love translation even more, since it gave me the push that I needed to open myself to discovering the unknown.

John Berry defines acculturation as “the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members” (2005, p. 698). However, the barrier between keeping in touch with your culture and remaining open to other cultures becomes very thin because it is very easy to lose touch with your roots if you are determined to do everything that you can to adapt to your new environment. This can be especially confusing for young adults, as they no longer know where they belong. I remember feeling lost at times because I could not find a place to sincerely call “home.” My life in France felt like a full-time job where I had to work my hardest to find some people to like me, and my life in my home city felt small and distant, filled with a lot of people I used to call friends and some people who decided to stick around in my life to this day. I didn’t belong to either place.

Coping With the Imposter Syndrome

Studying translation already comes with its own set of difficulties, since we consistently strive to be the best and to reach the same level of fluency in foreign languages as we have in our native tongue. Studying translation while working exclusively with foreign languages, with little to no contact with your native tongue, is quite a rollercoaster. One thing that I share with a friend in a similar situation, a person studying translation in France, whose native tongue isn’t integrated into the master’s they’re doing, is the imposter syndrome and the anxiety that comes with it. Picture this scenario: You’re making your best efforts to obtain good grades despite the difficulties of studying foreign languages exclusively, the results are not very encouraging, and your proficiency level seems to be insufficient. On top of that, you’re quadrilingual and you use most of these languages on a daily basis. Because of that, your coherence seems to deteriorate, especially in your native tongue, which is the least used among them. The result is a discouraging feeling that you are not doing enough, you aren’t making enough efforts, and you are failing in the one thing you are supposed to excel in. The problem is not so black and white: There are grays and shades of color everywhere. Yet, you start feeling like a fraud, like your achievements don’t mean as much as they should, which only adds to the stress and anxiety you’re already feeling.

Learn to Appreciate Your Self-Worth

In the end, any hardship can be overcome once you realize that doubting yourself is part of the process, and that asking for help, whether it be professional help or just friends and family, is nothing to be ashamed of. Stepping outside your own thoughts and getting an outside opinion is essential. Feeling discouraged is natural and human; yet, it is important to remember the person you are now has acquired experience and has achieved milestones the old you could only dream of, and that no effort is ever made in vain.

Being an international student in translation is a rewarding experience from all perspectives. Having the chance to practice and improve your language skills with native speakers, the opportunity to discover all the layers of the language, which incorporate their cultures, traditions, and their way of life, is a gift in itself. I am nothing but grateful to have lived through it all: the good, the bad, and the in-between.

Bibliography

“2023 Key Figures: Europe Is the Leading Host Region for Mobile Students.” n.d. Campus France. https://www.campusfrance.org/en/news/key-figures-2023.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

Li, W. (2022). Mental problems of ‘Language Gap’ for the international students. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 631, 1178-83. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.220105.217.

MacIntyre, P. D. 1999. Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning (pp. 24-45). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Smith, R. A., & N. G. Khawaja. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004.

Details

- Publication date

- 3 April 2024

- Author

- Directorate-General for Translation

- Language

- English

- Romanian

- EMT Category

- Activities of the EMT network