Could this shape our trainees’ future professional activity? (Source: personal picture)

An introduction to video game localisation and its challenges

Ten years ago, nobody would have suspected that video game localisation would acquire such importance in translation curricula. I mean… how did video game aficionados (the so-called “geeks”) bring about such changes in the way we teach translation practice in order to prepare students for the professional market? Is translation not supposed to be related to technical or literary texts, and are we not supposed to challenge our students rather than ask them to translate such “irrelevant contents” as video games?

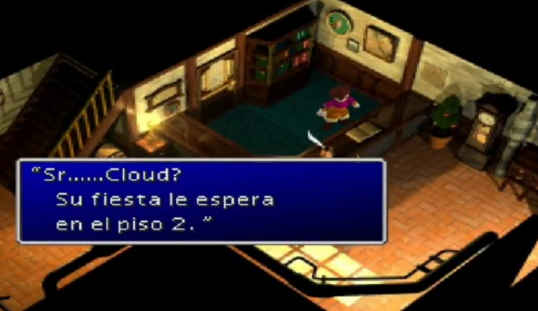

Well, to tell the truth, video game localisation is far from easy, nor is it irrelevant. As a matter of fact, the estimated value of the global video game localisation industry was $1.38 billion in 2018, and is predicted to “aggressively increase year-on-year” (Bussey, 2020). As for it being “easy”, one should be reminded of famous localisation “fails” observed throughout the years. Several examples can be found in Final Fantasy VII, issued in 1997.

https://twitter.com/SimplyMartis/status/1014606483001167873/photo/1

For instance, in this scene, the English wording (translated from Japanese) “Your party awaits upstairs” was badly translated into the Spanish sentence “Su fiesta [sic.] le espera en el piso 2”, instead of “Su equipo le espera en el piso 2”, since Cloud, our favourite hero, did not take part in any “raving” party: his “team” of fellow travellers was only waiting for him in the inn’s bedroom. Of course, some of these errors are funny, and do not have consequences on players’ gaming experience. Yet, in some instances, such problems can lead to confusion for players, hence the necessity of implementing localisation classes in EMT universities, with a view to preparing students to access the localisation market and avoid such problems.

The objective of this contribution will be to describe initiatives in terms of localisation taken by the University of Mons, with a view to better integrate EMT objectives in our translation curriculum.

Video game localisation, translation strategies and EMT objectives

First of all, localisation is recognised as one of the key competences to be taught to students in EMT programmes. Indeed, the 2017 EMT model states that students need to know how to “Translate and mediate in specific intercultural contexts, for example, those involving public service translation and interpreting, website or video-game localisation, video-description, community management, etc.” (p. 8). The 2017 written version of the competence framework also states that localisation is one of the skills to be included in the curriculum of EMT applicants (p. 7).

There are several reasons why localisation should be considered as an independent skill, which is really different from translation, though they share some characteristics. While it is true that both translation and video game localisation require a linguistic transfer from a language to another, several factors which are particular to video game localisation have to be taken into account.

First of all, the very nature of the audience influences the way such texts need to be localised. In the case of video game localisation, the audience is made of players, which need to perform the actions described by a text appearing on a screen. This means that the audience is not passive, since the textual input represents a guide through the universe of a video game. While translation can be target-oriented, this is particularly the case for video game localisation, since players who play the localised version of a game need to enjoy the same experience as players who play the original version. The commercial aspect of video games is of key importance here, since a badly localised game will receive negative feedback from players online… which will hinder the sales. Therefore, the very spirit of the game (including the names of protagonists or places), must be linguistically transferred, without any content loss which could affect the players’ experience.

This would seem relatively easy without any technical constraints. Yet, video games are, as highlighted above, played on a screen, where the number of characters is limited. Though it would be nice to use an entire paragraph to recount Link’s adventures on his way to save Princess Zelda, two main elements make it impossible: the text boxes in which the narrative text or the dialogues appear, and the very scene of the game being played at a determined time. On the one hand, text boxes can only contain so many characters, meaning that the text appearing in the box at any moment has to cover the same content in source and target language. This can prove rather problematic, for instance, in the case of localisation from English into French, the latter usually being more prolific and less concise than the former, which sometimes require people in charge of localisation to be imaginative in order to preserve the meaning while not exceeding character limitations. A second element to be taken into account is the scene appearing on the screen, which can influence translation context. For instance, let us imagine a scene where a character is walking towards a fish market and says, “Oh, I see fish over there”. In such a scene, the person in charge of localising the game into French should be careful to translate this idea by “Oh, je vois du poisson là-bas” rather than “Oh, je vois des poissons là-bas” (which would imply that said fish are alive).

Now that the main challenges of video game localisation have been highlighted, the time as come to describe how we, at the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, are currently working to integrate this practice into our translation curriculum.

Video game localisation @UMONS

Considering both the growing commercial weight of the localisation industry and the need for EMT universities to implement localisation teaching in their curricula, we decided to tackle this challenge by implementing several initiatives to help both teachers and students get acquainted with localisation practice.

First initiative: “Gaming and Gamification” group

The very first initiative to be mentioned is our participation in the “Gaming and Gamification” working group. This group is not exclusive to the University of Mons: it came from a collective effort from stakeholders in the Belgian province of Hainaut.

The main objective of this group is to create an interdisciplinary network of companies and services interested in the video game industry within our province and, eventually, the French-speaking part of Belgium, Wallonia.

Our participation in such a project represents a precious opportunity for our university: apart from being the first French-speaking Belgian university to take part in such a large project in the context of the video game industry, this provides us with a unique opportunity to learn from other stakeholders and remain up to date with the latest developments of practices within the video game industry.

Moreover, this project also enables us to develop partnerships with video game companies here in Belgium, which provides our students with internship and collaboration possibilities and helps them build contacts with the professional world.

Finally, we should underline that, while this project mainly involves Belgian stakeholders, we are open to external collaborations. For instance, in the very field of video game localisation, our Faculty of Translation and Interpreting is currently establishing a partnership with the University of Bourgogne (France) to share best practices and learn from each other.

Second initiative: Masters’ theses in video game localisation

The second main initiative we are implementing is directly linked to our students. Last year, we underlined the possibility for them to write a Master’s thesis in the field of video game localisation (i.e. localise a video game or carry out a piece of research in the field of localisation). This had never been done before, and it came to many students as a surprise: they were ecstatic to learn that they did not necessarily had to translate a regular book in the framework of their Master’s thesis.

This year, five students chose to localise a video game for their thesis, either from English into French or from Russian into French. Supervising them represents a thrilling challenge for us lecturers: it is the very first time for all of us. We also have to get acquainted with localisation norms and constraints, in order to guide them properly and help them produce high-quality work.

Two of these students, Alexiane Mahieu and Noéline Urbain, accepted to describe the way they perceive video game localisation, and the reasons why they think localisation classes are crucial to future professionals.

Alexiane: Since I was little, I have always been passionate about video games, and I always played them in my mother tongue: French. This would not have been possible without the work of translators. From dubbing to subtitling, their work is important because it enables many people to enjoy video games, which are nowadays considered as works of art on their own. Most video games are created in English or Japanese, languages that are not spoken by everybody. Yet, the objective of video game creators is to make their game accessible to as many people as possible. Moreover, video games contain more and more content, which makes localisation more and more difficult, with respect to integral dubbing, which did not exist in the video game industry twenty years ago, and texts, denser and more technical than before. This increasing complexity calls for greater abilities, which would make localisation classes essential to all people who, like me, would like to contribute to the development of the field they are passionate about. [Our translation]

Noéline: […] Video games often contain many puns and cultural references that make them impossible to be translated by machine translation. A badly translated game is, at best, not fun to play and, in the worst cases, impossible to understand. It is therefore interesting to teach the fundamentals of localisation to Master’s students to provide them with additional professional opportunities on the translation market. Moreover, localisation tasks differ from what we are usually taught at university, and students would really benefit from a class which would teach them to tackle the numerous challenges linked to video game localisation. When one starts to localise a video game, it is necessary to learn not to exceed on-screen character limits, to know the video game jargon, and, most of all, to manage to adapt contents to another culture. When localising a game, one also benefits from more freedom than when translating a specialised text, which makes it necessary to be able to translate insults or contents that can sometimes be violent […]. [Our translation]

In a nutshell, the students who choose to localise a video game in the framework of their Master’s thesis seem to be aware of the professional opportunities that localisation can provide them with. Furthermore, they provide us with an accurate overview of the main challenges and constraints of video game localisation. Without any doubt, their Master’s theses will be highly relevant and very interesting to read!

Third initiative: LocJam

Last but not least, students in the first year of Master’s were offered to take part in a global initiative in the field of video game localisation: the LocJam project (https://itch.io/jam/locjam-wmhd).

This project was a three-day localisation “marathon” which took place from October 8 (00.01 am) to October 10 (11.59 pm). This worldwide localisation competition consisted, this year, in localising (in our case, from English into French) a ~3500-word video game about mental health. Students were allowed to work in teams (I allowed teams made of up to six students) to localise the whole game in three days. I was thrilled to see that no less than 65 students of my Translation Technology class decided to take part in this project. In the end, the localised text produced by a group of participants (hopefully, participants from the University of Mons) will be chosen to become the official translation of this game!

The texts produced by our students and the feedback they will provide will help us build a coherent and relevant localisation class, based upon their difficulties and the aspects they considered important.

See you in a few weeks for the results!

Conclusion

Through this contribution, we wanted to highlight the relevance of localisation projects and classes within university classrooms. Our main objective was to describe the initiatives implemented by the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting (University of Mons) to help students get familiar with the localisation process.

Though we can only initiate students to localisation in the framework of our Translation Technology classes today, we hope that in the future, thanks to all these ongoing projects, we will be able to implement proper and thrilling localisation classes in the years to come!

References

EMT expert group. (2017). Competence framework 2017. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/emt_competence_fwk_2017_en_web.pdf

Bussey, Steven. (2020). An Overview of the Games Localization Industry in 2020 (Andovar blogs). Retrieved from https://blog.andovar.com/games-localization-in-2020.

Details

- Publication date

- 15 October 2021

- Language

- Bulgarian

- Dutch

- English

- Italian

- EMT Category

- Activities of the EMT network

- Translation competences