Industry vs academia

The discrepancy between academic training results and industry demand is a heavily discussed topic on both sides of the translation world. One such example is EUATC’s language industry report for 2020[1], which states that ‘new graduates still lack market awareness and process knowledge’ and ‘training impact disappoints 1 out of 5 translation companies’. This gap between market reality and academic preparedness is commonly observed in localisation. Over the past few decades, software, website and multimedia localisation grew within the translation paradigm to form domains of their own. Currently, companies declare localisation as a service separate, or at least complementary, to translation in industry reports. For instance, in Nimdzi’s 2021 ranking of the 100 largest language services providers in the world[2], the most commonly offered service offered by the companies included is ‘translation & localisation’, covered by 97.5% of providers, with 45 out of 100 LSPs explicitly mentioning localisation; 13 – media localisation and/or video games and movie translations; 10 – technology and/or IT, in their portfolio, as well as with ‘technology, software & IT’ ranking as the most prevalent industry segment. Nimdzi experts also predict a growing demand for localisation as a result of the pandemic, the 5G implementation and other contemporary factors. At the same time, EUATC states that ‘software and media localisation made up about 6% of all revenue’ in the language industry for 2020 and determine localisation as one of the areas in which language professionals pursue training in their continuous development.

EMT and localisation

Where does the EMT stand in all of this? In EMT’s competence framework, localisation is mentioned under number 8 (in translation competence):

Translate and mediate in specific intercultural contexts, for example, those involving public service translation and interpreting, website or video-game localisation, video-description, community management, etc.[3]

Website/video-game localisation here is considered a specific intercultural context. Being defined as such would imply it requires relevant translation shifts and considerations, aligned with all its interdisciplinary aspects – from linguistic to technological. In order to review how this competence is reflected in the EMT members’ curricula, we conducted a study of all listed EMT members’[4] websites, sorting the master programmes according to one factor – whether or not they mention and/or include localisation in their curriculum.

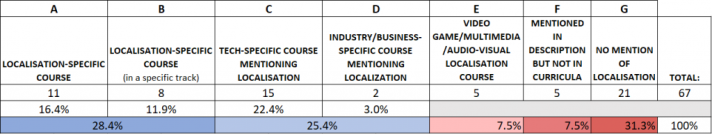

The information provided online was sufficient for a preliminary analysis on 80 of the 85 programmes listed. After reviewing all 80 programme descriptions and curricula, the programmes were divided into 6 main groups that were further divided into 4 types of programme (1. programmes in general/professional translation or translation studies; 2. programmes with a focus on translation technology or technical translation; 3. programmes with a focus on audio-visual translation; and 4. programmes with a focus that does not suggest localisation being covered):

- programmes which are not split into specialization tracks and offer a course in localisation;

- programmes split into specialization tracks that offer a course in localisation;

- programmes that offer no localisation-specific course, but integrate localisation in another course with a focus on translation technologies;

- programmes that offer no localisation-specific course, but integrate localisation in another course with a focus on industry practices;

- programmes that offer a course on audio-visual/multimedia localisation only;

- programmes that do not mention localisation in their curricula, but do mention it as a competence in the programme description;

- programmes that do not mention localisation on their pages whatsoever.

It is crucial to note that, apart from the programmes which provided no relevant information online or those where the information was insufficient, there were some where the information had not been recently updated, which could also affect the results.

Results

Out of the 80 programmes analysed, six were of types 3 and 4. Two were focused solely on audio-visual translation – and both falling within type (e) – and 4 were with a focus that does not suggest localisation being covered – however, only three of these were of type (g) as one offered a tech-specific course mentioning localisation (c). The technology-oriented programmes were seven, 3 of which were of type (a); 1 of type (c); 1 of type (d); 1 of type (e); and 1 of type (g).

The focus of the current analysis, as well as all respective conclusions, is on the programmes of type 1 – numbering 67 in total. The number of programmes in each of the six types can be seen in Fig. 1 below.

The results indicate that almost 54% of all programmes offer either a localisation-specific course or a course mentioning localisation (or around 61%, if audio-visual localisation courses are included). Slightly less than half of those offer localisation-specific courses, meaning courses which have the hours to approach localisation from different perspectives and discuss its various aspects in more detail. Slightly over one fourth of all programmes mention localisation only within a course with a focus on translation technology, some of which mention localisation in the course title, while others only mention it within the course description in relation to the competences acquired. Almost 40% do not offer a localisation-related course, one fourth of which, however, mention localisation in the general programme overview.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that these are preliminary and limited results that would undergo further analysis of peculiarities, exceptions and dependence on different factors than those covered, several conclusions can still be drawn. Firstly, although all these programmes are of general nature and offer various specialised courses in different translation verticals, localisation is still not heavily covered within their curricula (unlike literary translation, for instance). Secondly, the number of programmes which approach localisation from a CAT tool perspective only shows that many programmes offer a one-sided view of localisation which does not necessarily cover localisation-specific translation problems. Therefore, it is just slightly below one third of students in general translation programmes within the EMT who have the opportunity, while still in academic training, to delve into localisation details such as the localisation process, its interdisciplinary, the various competences required, and the implications due to the combination of linguistics and technology inherent to localisation.

[1] European Language Industry Survey 2020 Before & After Covid-19 //ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/2020_language_industry_survey_report.pdf (07.02.2022)

[2] The 2021 Nimdzi 100: the Ranking of Top 100 Largest Language Service Providers <https://www.nimdzi.com/language-technology-atlas/> (08.02.2022)

[3] EMT Competence Framework <https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/emt_competence_fwk_2017_en_web.pdf> (09.02.2022)

[4] List of EMT members <https://ec.europa.eu/info/resources-partners/european-masters-translation-emt/list-emt-members-2019-2024_en> (02.02.2022)

Details

- Publication date

- 14 February 2022

- Language

- Dutch

- English

- French

- Italian

- EMT Category

- Translation competences